2021 Must Be the Year to Reconcile Humanity With Nature

Feb 15, 2022

These were the words of António Guterres, the UN secretary-general, in an address to the One Planet Summit on December 2020.

The world has raced to find ways to combat COVID-19 but perhaps, we need to have a wider perspective on where the root of the pandemic is and work from the inside out. The actions we undertake today will prevent us from fixing humankind with bandaids in the future.

As we prepare to slowly go back to a life similar to what used to exist before Covid came, it is important to reflect on the lessons we have learned and take action to restore ecosystems for the future.

Planet Earth gave us the loudest wake-up call in 2020, but there is still hope.

In 2021, for the sake of humankind, we must take massive action and believe we are able to commit to living in harmony with nature again.

New Scientist Magazine has recently published an article written by Graham Lawton on how to fix the biodiversity crises. Below you will find snippets of the content to help bring clarity to the matter.

"The numbers are stark:

More than 70 per cent of ice-free land is now under human control and increasingly degraded. The mass of human-made infrastructure exceeds all biomass. Humans and domesticated animals make up more than 90 percent of the mammalian mass on the planet. Our actions threaten about a million species – 1 in 8 – with extinction (see “Biodiversity: A status report“).

All that has happened in a blink of an eye, geologically speaking. “If you compare Earth’s history to a calendar year, we have used one-third of its natural resources in the last 0.2 seconds,” Guterres said in Paris.

The signs are that covid-19, a scourge caused by our dismissive regard for nature, might finally have focused minds.

The question is, what needs to be done – and can we do enough in time?

“The world is facing three major crises today: the loss of biodiversity, climate change and the pandemic,” says biologist Cristián Samper at the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York. “They are all interrelated, with many of the same causes and solutions.”

“But we’re at a stage now where conservation is no longer enough. We also need to heavily invest in restoration.” - Tim Christophersen at the UN Environment Programme (UNEP)

Ecosystem restoration will be the key to success or failure over the coming decades.

It takes many forms, depending on the ecosystem and how badly degraded it is. At one end of the spectrum is passive rewilding, which simply means getting out of the way and letting nature do its thing. “It’s amazing, the capacity that nature has to heal itself,” says ecologist Paul Leadley at the University of Paris-Saclay in France.

Small-scale rewilding projects such as at Oostvaardersplassen in the Netherlands, where an area of reclaimed polder land has been given over to nature, have shown the way, but the ambition must grow – and is growing. In Europe, the biggest project aims to leave some 35,000 square kilometres of Lapland in northern Sweden and Norway to rewild. In North America, the Wildlands Network aims to link up protected areas in “wildways” in which animals can freely roam spanning Canada, the US and Mexico.

At the other end of the restoration spectrum is active engineering of entire landscapes with mass tree planting, removal of alien species and damaging infrastructure such as dams, and reintroductions of species.

This can be done. South Korea adopted an active reforestation policy in the 1950s following the Korean War. The total volume of wood in the country’s forests increased from some 64 million cubic metres in 1967 to 925 million cubic metres in 2015, and forests now cover some two-thirds of the country. The Green Belt Movement founded in Kenya by Nobel peace laureate Wangari Maathai has planted tens of millions of trees across Africa, and inspired many similar projects.

The headline target of the UNEP initiative is to restore 3.5 million square kilometers of land over the coming decade – slightly more than the size of India, or just over 2 percent of the world’s land surface. That is “incredibly ambitious”, says Strassburg.

“If we were to achieve that, it will be the fastest reshaping of [Earth’s] surface caused by us.” It won’t come cheap. According to UNEP, the upfront cost is about $1 trillion, no small change in a post-pandemic recession, although it is an investment with a high rate of return (see “What do ecosystems do for us?“).

A lesson of the past decade is that, where governments and other groups commit to protecting biodiversity, change can happen (see “Ten conservation success stories when species came back from the brink”).

Ultimately, success or failure will depend on progress in another key area: climate change.

Conserving biodiversity and restoring ecosystems will have positive knock-on effects for the climate. “Restoration is one of the most cost-effective tools to mitigate climate change,” says Strassburg: land-use change and increased plant cover can deliver up to a third of the reduction in greenhouse gases that we need.

Ultimately, the next decade needs to be about synergy, with biodiversity initiatives, efforts to combat climate change, and other international programs such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals converging on the ultimate target: harmony with nature by 2050.

Crucially there is still time, just, to manage the pivot from the Great Acceleration to a Great Restoration, an era when humanity learns again to live sustainably and in harmony with nature.

Choosing to have faith in humankind and gratitude for the wise nature around us.

Much LOVE,

Sources:

- One Planet Summit

- New Scientist - Rescue plan for nature

- New Scientist - Graham Lawton

- New Scientist - Biodiversity in crisis

- New Scientist - Is life on Earth really at risk?

- New Scientist - Can we really restore ravaged nature to a pristine state?

- New Scientist - Planting a trillion trees really can help

- New Scientist - What do ecosystems do for us?

- New Scientist - Ten conservation success stories when species came back from the brink

- New Scientist - Climate Change

- Biodiversity: A status report

- Wildlife Conservation Society

- Ewilding Europe

- Wildlands Network

- UNDP - Sustainable forestry

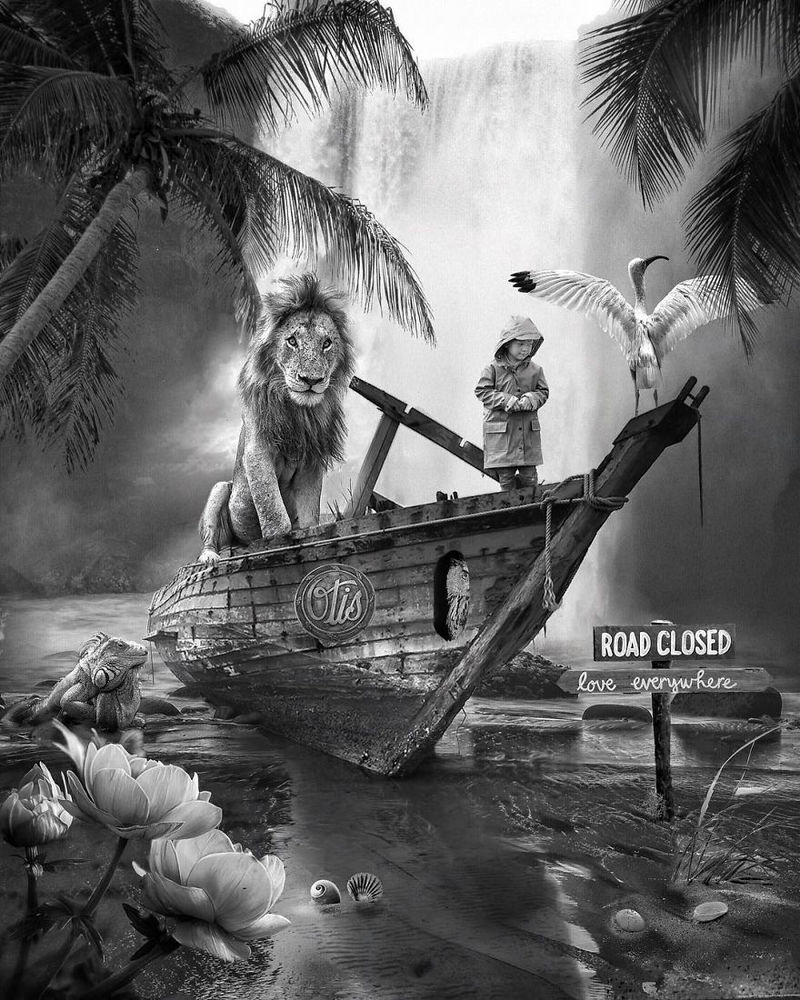

Images:

- 1st and 3rd: Marcel Van Luit

- 2nd: Farmland encroaches on the forest around the Debre Mihret Arbiatu Ensesa church in Ethiopia - Kieran Dodds/Panos Pictures

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.